In 1992, I was featured in the St Paul Pioneer Press Express section with an article about my electronic music studio, and my MANY opinions I had to share.

The article was written by a dear friend of mine, Mike Mattison. Here are the scans, plus a transcription of the article. Below, I’ll post a few thoughts for context!

The Reay World – St Paul Pioneer Press 1992

“Welcome to the Death Star!" says composer Jim Reay, as he makes a dramatic gesture around his electronic music studio. "The Death Star was that ridiculous technology-laden instrument of death used by the Empire in 'Star Wars.' "

Reay taps a few power switches and logs onto his system. Keyboards, drum machines and color screens come to life, blinking red: "I am Locutus of Borg." mutters a villainous, robotic voice. "Resistance is futile!" Reay programmed that message to spring on himself each day; a not-so-gentle reminder of his humanity, his "artistic self.," which is in danger of being sucked irrevocably into cyber-space.

For those of you unfamiliar with "cyber," the ubiquitous buzzword is hip-speak for "cybernetics," which, according to the dictionary, means: "the comparative study of human control systems [i.e., the brain] and complex electronic systems [i.e., computers]."

For all practical purposes, Reay is a living, breathing study in cybernetics. His livelihood and creativity are played out in synthesizers and programmable noisemakers. Mano-a-machine. Knowing this, it's strange to hear him ponder the following: "Cyber ... cyber ..." He rolls the sound around in his mouth. "I hate that word."

To stay alive, Reay freelances, writing film and theater scores; but his bread and butter is "Sequencing," translating popular songs into a digital format so they can be replayed by virtually any musician anywhere with standardized equipment; sort of a gentrified karaoke.

Reay's work might seem highly specialized, but the extent to which computers like his are making and sustaining today's music would shock many listeners. Watching television, even the commercials, Reay can spot fake horn sections, reveal computer violins and expose TV themes that are entirely synthetic.

"All that news stuff is completely programmed; 'Entertainment Tonight'; 'The Simpsons'; cop shows... Who's gonna pay an entire orchestra? Big-budget movies, and that's it."

Reay looks slightly panic-stricken as he gives example after example. "Every bit of hip-hop, most country music ... Sounds of Blackness! There's a good local example. It took 'em Jimmy Jam's synthesizers to get famous. And nobody does drums anymore, OK? It's a dead, dead art. Remember all those drummers who freaked out in the '80s? Roger Taylor [former drummer for Duran Duran] had a nervous breakdown during the making of the song “wild Boys”. He kept saying “You’re not gonna let me play?” And they kept saying “No! We’re not gonna let you play”. That was the song that broke him”.

Reay graduated from Macalester College with a degree in musical composition along with a special concentration in percussion – marimba to be exact. His propensity for shaping sound with technology, however, began at a very early age. He began teaching himself computers in 1979, a time of rapid advancement in the sound-technology industry.

Hearing Reay talk about his trials and errors is sort of a crash course in the history in electronic music itself. He witnessed the birth of cyber, and although he remained smitten by the phenomenon, their bond would not be infallible.

“In the late ‘70s my family got a computer in the house. I learned to program it; really simple programs you could copy out of a book. So, like, in the end you’d have these really jerky space-invaders games.”

A family friend, in tune with Reay’s interest, lent him a Moog Prodigy keyboard, one of the first synthesizers that didn’t take up the entire research wing of a state university. But it was a hefty machine nonetheless, wide and hollow. “It had knobs and wheels on it. You could manipulate the sound, do things you were unable to do with a piano.”

His curiosity piqued. On the advice of the same family friend, Reay purchased a keyboard, a Yamaha DX9. The new keyboard was long, black, and streamlined. It sounded more “real” than the Moog. “The DX9 was really the start of the ‘affordable’ digital era in synthesizers” he says.

The digital era! Synthesizers!

Reay asks that you not fear these terms. The distinction between the DX9 and the Moog is a small matter of “digital” vs “analog”.

“Analog is an electronic process,” Reay says. “If you press a key on the keyboard, it starts an electronic reaction that will create a particular sound. On digital keyboards the sounds are already stored on computer chips. When you press a key on a digital keyboard it simply releases a ‘stored’ sound. Digital is a logical process, Analog is electrical”

And so, Reay was swept into the digital age – buying, selling, adding, and trading equipment. As his studio grew, so did his creative possibilities, thanks in part to the advent of “Musical Instrument Digital Interface”. MIDI (pronounced “Mid-dy”) is a standardized method of telling a keyboard which notes to play from a separate keyboard or computer.

MIDI is a way to simultaneously “coach” your entire “team”. Reay could trigger an array of keyboards and drum machine with one hand while clutching a Jolt Cola with the other.

“But the early digital synthesizers were limited” he notes. “They weren’t expandable and didn’t have a lot of character. The sounds they were capable of, you could exhaust. It was planned obsolescence. Every year there was a new ‘sound’ and that’s what you’d hear on the radio”.

The copy-cat syndrome in popular music was traceable to a single computer chip. “For example, from 1986 to 1988, the big sounds were the Roland D-50’s ‘Digital Native Dance” and “Fantasy”. The Fairlight “Vocal” was also pretty big. It was in all those Heaven 17 songs and Duran Duran songs.”

Reay retreated. He spent hours away from his equipment, estranged. To raise his spirits, he moonlighted as a drummer for a very bad punk-rock band. “The band was called ‘Karl’, and we were very, very bad” he admits.

Technology-wise, the pressure was on’ upgrade or die. Each week, a new product trumped an old product and spread its “sound” throughout the industry, only to mysteriously pass out of style, hat in hand with the hit songs it produced.

Of course, this is the oversimplified explanation, the fairly-tale version. But to go – chip by chip, fuse by fuse – through the whole matrix of little leaps and inconsistencies is to ignore the larger dilemma: What was happening to music? The machine half of “cyber” seemed to be triumphing over the artist the 50-50 partnership was faltering.

“I knew I had to stop writing songs around the New Sound of the Year. I had to stop getting inspired and awed by technology and start using it” Reay says.

So, he decided to make do. He quit purchasing new machines, and he confronted what he already owned. “I started going back to analog keyboards, taking advantage of their knob interfaces and dials. I went away from preset sounds and started making my own.”

And therein lay the gray area, the X factor, the possibility. The cyber-train was picking up speed, charting its own course, and the only hope for Reay was to take stock of why he’d tangled with the technology in the first place. He found he was more interest in exploring his own capabilities than the synthesizers’.

“The fraud of this whole ‘cyber’ rage is that you have new and exciting buttons to push that give you results of your ‘own’. NO! A programmer in Anaheim is actually responsible for what you’re doing”.

Reay makes a wry face. “It’s all in how you put the technology to work. It like the concept of the piano. The piano doesn’t give you ideas, it’s a tool to put your musical ideas to work. The great composers didn’t say ‘Listen to how great this sounds! Tink! Tink! Tink!’ The composer works beyond the limitations of the medium and nobody is being a Franz Liszt with this stuff. Yet.”

30 Years Later - a few notes

I was a bit of a know-it-all, but that’s still true. My friend Mike really captured the essence of a conversation with 1992 Jimmy, and I’m thrilled to have this time capsule. THAT SAID, there are a few clarifications I’d like to make.

This was before the internet, and fact checking was somewhat lax. I know that I read the Roger Taylor quote in a magazine, and it stuck with me, but going back I can’t find the original source, and so I can only hope that this page does not become a point of controversy in the history of Duran Duran.

I also didn’t mean to be dismissive of Sound of Blackness - only to comment that these local legends hit the “big time” on radio once they partnered up with Jam and Lewis and got that produced sound. It’s less a comment on them, then the state of the industry at the time. No disrespect was intended.

Likewise, I now know that while Alf Clausen and Danny Elfman used synthesizers extensively in the composition process, that the Simpsons was actually one of the few shows that had a full orchestra for soundtrack. I picked a bad example.

My attitude towards “presets” has softened over the years, and much of my music has a base from a sample or preset from a synth, that I alter and make my own. But I stand firm that the “sound of the day” stuff of the late 80s/early 90s was really tiresome.

I’m aware that my synth history was not entirely accurate - that the there were many synths before the Prodigy that were affordable and portable (one example is in my lap above - the ARP Odyssey). This was something I could have clarified, but Mike was under deadline and my first view of the article was when it was published. We rolled with it.

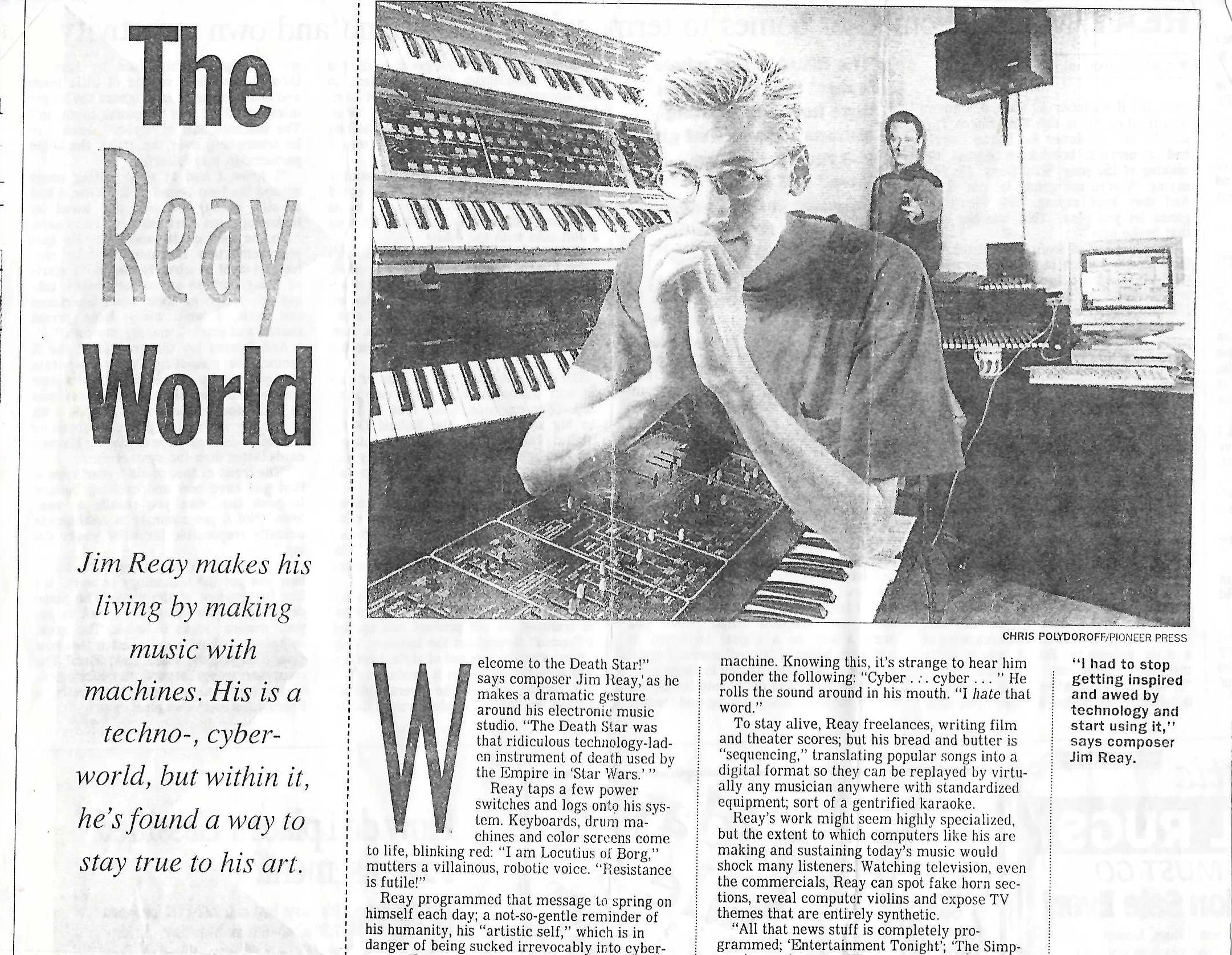

My main clarification however, is that while I did stop chasing the newest gear, I never stopped collecting gear - I actually took advantage of other people’s sound-chasing and bought a lot of really amazing synths that people were unloading in the early 1990s. In the picture above you can see a Memorymoog that I had got second-hand from a prominent local band keyboardist.

I’m grateful to Mike for this feature - it was a huge deal for me and my friends, and I got a lot of comments. I must say it never directly led to any WORK, but if my words helped inspire someone to get into synths and get creative, it was absolutely worth it.